Bartolini, who is a student-teacher in a first grade classroom at the Campus School, says she is picking up on strategies to use with the elementary participants at Project Coach sessions. Going from the highly structured school day to the after-school atmosphere can be challenging, says Bartolini. At the same time, she is gaining useful experience with solving problems spontaneously, figuring out new ways to motivate and engage young people.

Bartolini also thinks of student-teaching and PC as parallel experiences. As a student-teacher, she plays a role quite similar to the High School coaches with PC. She notices strategies her lead teacher uses to encourage her as a new teacher, like accentuating the positive. Bartolini says that this serves as a reminder to always compliment the HS coaches, giving them encouragement along with increased responsibility.

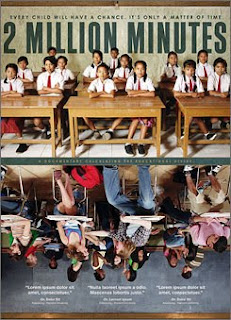

Bartolini (left in photo

In her first grade classroom, Bartolini gets to know her students in very different ways, through reading and recess both. As she gets to know her students, she sees what reading strategies work best. She says that the first graders were really comfortable with her at the very beginning of the year. While first graders are eager to "hold your hand at recess," Bartolini says, high school students can sometimes hold back until they feel they know who you are.

According to PC Fellow Kathleen Boucher, student-teacher in a fourth grade classroom at the Campus School, she feels like she transitions into a head teacher with Project Coach. While she looks for advice from her head teacher at her teaching placement, her high school coaches look to her for help with the elementary participants after school. At times, Boucher notes, she jumps in and becomes the leader of both groups. According to her, it is a sometimes a challenge to bring the structure of the classroom to the athletic field. One management technique she brings from student-teaching is for giving directions, whispering "If you can hear my voice, clap once." Other strategies she finds helpful include rotations of activities, like during the indoor sessions (due to rain) and, now, with the options of dance and track during soccer sessions. Boucher is interested in seeing how the basketball season compares with soccer, and in learning more about what the program means to elementary-aged participants.

Overall, Project Coach Fellows learn about children across ages, races, and classes. They work with them both in the classroom and after school, at the desk and on the field. They also help with academic assistance by helping to track grades and improve on homework. Undoubtedly, these experiences will help to make them insightful and effective teachers in the future.